Vertigo is defined as:

“a condition in which somebody feels a sensation of whirling or tilting that causes a loss of balance.”

To describe the sensation of vertigo, patients often use words such as dizziness, giddiness, unsteadiness, or lightheadedness.

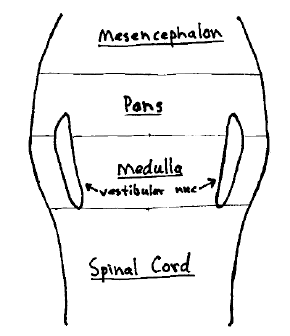

The neurological vertigo center is called the vestibular nucleus. The vestibular nucleus is located in the brainstem. It occupies a position that extends from about the level of the atlas in the medulla cephalically to about the bottom third of the pons.

The vestibular nucleus will reach excitation threshold and depolarize, creating the sensation of vertigo, as a consequence of the afferent information that enters it. This afferent information and subsequent vertigo sensation can be either normal or abnormal. As an example, if one subjects their body to a spinning event, a normal sensation of vertigo may arise. In this case, the sensation of vertigo is as a normal consequence of the spinning.

The etiology, diagnosis, and treatment are self-evident: stop spinning and the sensation will subside.

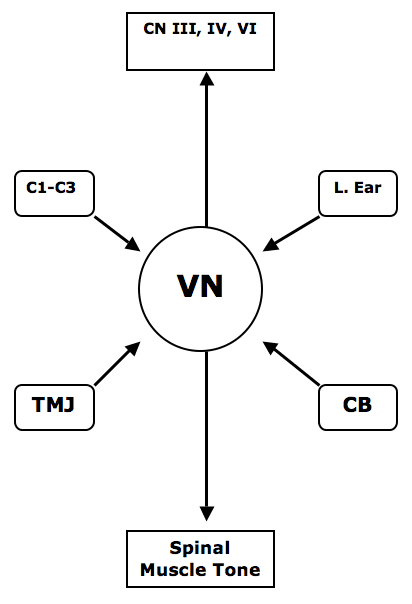

The afferent information that enters the vestibular nucleus and are thus capable is initiating a sensation of vertigo, can arise for a number of sources. The classic sources are these four:

1) Labyrinthine Inner Ear

Problems of the vestibular apparatus of the inner ear will depolarize the vestibular component of the eighth cranial nerve, depolarizing the vestibular nucleus and creating the sensation of vertigo. The problems of the vestibular apparatus can be anything from canalithiasis to infection. Also, the vestibular nerve to the vestibular nucleus can depolarize as a consequence of normal experiences that influence the inner ear, such as spinning, riding in a boat (sea sickness), etc.

Canalithiasis is the pathological diagnosis for the sensation of vertigo that occurs as a consequence of dislodged mechanical particles in the semicircular canals of the inner ear. The subjective diagnosis is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or BPPV. This type of vertigo is so named because:

Benign: the vertigo is not caused by a serious pathology such as infection or malignancy

Paroxysmal: the bout of vertigo last for a short duration, typically 20 – 60 seconds; an uncomfortable sensation of lightheadedness may persist for several hours

Positional: the bout of vertigo is triggered by putting the head into a specific position

Vertigo: for the sensation of spinning

The mechanical treatment of canalithiasis (BPPV) involves the precise positioning and timing of the head through a series of maneuvers in an effort to move the offending particles along the semicircular canals towards the utricle, which is an inert location. This technique was pioneered by physician John Epley, MD, from Portland Oregon, in 1992 (1). This technique is very successful in the appropriate patient. A PubMed search of the National Library of Medicine database (January 2010) finds more than 100 studies on the technique.

2) Cerebellum

The cerebellum is neurologically connected to the vestibular nucleus. In their 2001 book Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System, Robert Baloh, MD, and Vincente Honrubia, MD note that the cerebellum “provides a major source of input” to the vestibular nucleus. Dr. Baloh is Professor, Department of Neurology and Division of Head and Neck Surgery, UCLA Medical School; Dr. Honrubia is Professor and Director, Division of Head and Neck Surgery, UCLA Medical School. Consequently, cerebellar problems, or aberrant mechanically driven afferents to the cerebellum, can fire to the vestibular nucleus, creating the sensation of vertigo.

3) Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

It has been shown that temporomandibular joint afferents will fire to the vestibular nucleus, creating the sensation of vertigo. This was first reported in the Journal of Laryngology and Otology in 1965 in an article titled (3):

Nystagmus and Vertigo Produced by Mechanical Irritation of the Temporomandibular Joint-space

Consequently, temporomandibular joint dysfunction can be an afferent cause of vertigo sensation. Treatment is to the dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint and its afferent neurology. Temporomandibular joint surgery has been shown to correct symptoms of vertigo (4). Successful conservative management of patients with temporomandibular disorders and vertigo can show improvement in vertigo symptoms in up to 100% of patients (5).

4) C1 – C3

It has been known for more than three decades that the injection of saline irritants into the deep tissues of the upper cervical spine will create the sensation of vertigo in normal human volunteers (6). This cause of vertigo is classically termed cervical vertigo.

Clinicians have documented a relationship between cervical spine trauma and the symptoms of vertigo (8). In her chapter titled “Posttraumatic Vertigo”, Dr. Linda Luxon (7) notes that this vertigo can be explained by “disruption of cervical proprioceptive input.”

She further asserts that the major cervical spine afferent input to the vestibular nuclei “arises from the paravertebral joints and capsules, with relatively minor input from paravertebral muscles.”

The implication of clinical application to these findings is that dysfunctional upper cervical spinal joints and their capsules can alter the proprioceptive afferent input to the vestibular nucleus resulting in the symptoms of vertigo; treatment would be to improve the mechanical function of these joints.

CN Cranial Nerves

III oculomotor

IV trochler

VI abducens

C1-C3 Upper cervical joint capsular afferents, C1-C3

LE Labyrinthine Ear

VN Vestibular Nucleus

TMJ Temporomandibular Joint

CB Cerebellum

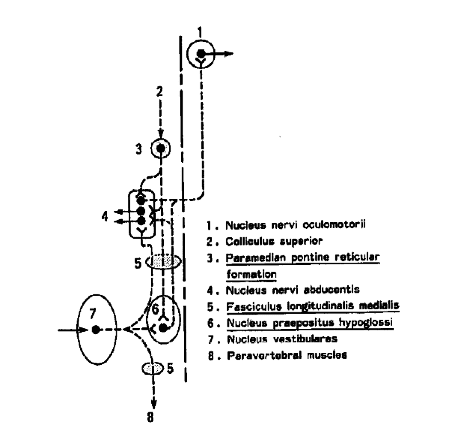

The vestibular has a neurological pathway that ascends and communicates with cranial nerves III (oculomotor), IV (trochler), and VI (abducens). These three cranial nerves (III, IV, VI) all move the eye. This is why vertigo is often associated with nystagmus. The vestibular nucleus also exerts control over spinal muscle tome (#8 in drawing below). This vestibular control of spinal muscle tone is important to chiropractors who maintain that aberrant mechanical afferent input into the vestibular nucleus will manifest as a recumbent functional inequality of leg length; improvement in mechanical afferent input to the vestibular nucleus will improve the symmetry of spinal muscle tone and equalize leg length inequality.

This drawing from the journal Spine (9) shows the neurological connections between the vestibular nuclei, the cranial nerve control of eye movement (CN III, IV, and VI), and the tone of the spinal muscles:

Drs. Baloh and Honrubia (2) note that the normal functional relationship between the vestibular nucleus, the control of eye movement, and the tone of spinal muscles can be disrupted by “electrically stimulating the capsules of the upper cervical joints.” Once again, this implies that mechanical dysfunction of the joints of the upper cervical spine can initiate vertigo, nystagmus, and alterations of spinal muscle tone; treatment is to the dysfunctional cervical joints.

••••

In 1998, an article appeared in the European Spine Journal titled (11):

Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction

The authors defined “dysfunction” as a reversible, functional restriction of motion of an individual spinal segment or as articular malfunction presenting with hypomobility. The authors also state that upper cervical spine dysfunctions can cause vertigo, and they cite 13 references to support the premise. They explain the vertigo as a consequence of disturbances of the proprioception from the neck. They cite an additional 4 references to claim that only dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine can cause vertigo, noting that anatomical studies identify links between cervical spine receptors and the vestibular nuclei.

In this study the authors used 50 patients who were referred to rule out a cervical spine problem as a cause of vertigo. All patients displayed symptoms of dizziness, and preceding ear examination and neurology examination were equivocal. A reproducible manual palpation examining technique was used to diagnose segmental cervical spine dysfunction. This type of examination is emphasized in chiropractic college.

The cervical spine dysfunctions were treated with mobilization and manipulative techniques. The patients subjectively rated themselves as:

“free of vertigo”, “improved”, or “not improved”, as follows:

GROUP A:

Thirty-one patients (31/50 = 62%), displayed dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine at the initial visit. These dysfunction were located as follows:

C1 in 14 patients (14/31 = 45%)

C2 in 6 patients (6/31 = 19%)

C3 in 4 patients (4/31 = 13%)

Combined dysfunctions were at:

C1 and C2 in 4 patients (4/31 = 13%)

C1 and C3 in 2 patients (2/31 = 6%)

C1, C2 and C3 in 1 patient (1/31 = 3%)

At the 3-month follow-up, 24 of the 31 patients of group A (77%) reported lasting improvement of vertigo, and 5 of them reported complete relief of vertigo. Seven patients did not improve (23%).

GROUP B:

Nineteen patients (19/50 = 38%), did not have dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine.

After 3 months of outpatient physical therapy, only 5 patients (26%) reported an improvement of vertigo, while the remaining 12 patients (64%) had vertigo of unchanged intensity.

The authors state the following conclusions:

“Physical therapy is more likely to succeed in reducing vertigo symptoms if these patients present with an upper cervical spine dysfunction that is successfully resolved by manual medicine prior to physical therapy.”

“We regard the cervical spine dysfunction seen in patients of group A as the principal cause of their vertigo.”

“In the presence of vertigo, our presented data suggests consideration of cervical spine dysfunctions, requiring a manual medicine examination of upper motion segments.”

“A non-resolved dysfunction of the upper cervical spine was a common cause of long-lasting dizziness in our population.”

••••

In 2002, an article appeared in the Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, titled (11):

A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin

These authors state that “cervical vertigo” was first published in the journal The Lancet in 1955 (12). However, my PubMed database search of the National Library of Medicine (January 2010) found 486 citations beginning in 1950.

In this article, these authors state:

“The term ‘cervical vertigo’ was introduced to describe dizziness and unsteadiness associated with cervical spine pain syndromes.”

“Increasing evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures.”

“Whiplash patients are likely to suffer from dizziness, vertigo and associated neck pain and disability resulting from traumatized cervical spine structures.”

“Cervicogenic dizziness, especially in whiplash patients, may result from disturbed sensory information due to dysfunctional joint and neck mechanoreceptors.”

“Dizziness and vertigo are common complaints of neck pain patients with 80 to 90% of whiplash sufferers reporting these symptoms.”

“Dysfunction or trauma to connective tissues such as cervical muscles and ligaments rich in proprioceptive receptors (mechanoreceptors) may lead to sensory impairment.”

“Emerging evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may commonly arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures such as joint and neck mechanoreceptors, particularly from trauma.”

In this study, the authors evaluated 180 consecutive neck pain patients over the age of 18 were recruited from the outpatient clinic. Of these, 71 patients (40.57%) reported neck pain resulting from trauma and 60 patients (33.5%) were suffering from dizziness. Patients were excluded if they had radiographic evidence of congenital anomalies, fracture/dislocation, inflammatory, infectious or other serious pathologies. Patients were asked to answer questions regarding demographics, history of injury/trauma and duration of neck pain, and presence of neck pain related dizziness/unsteadiness. Pain intensity was measured using two, 11-point numerical rating scales while disability was measured with the Neck Disability Index (NDI).

The authors note that dizzy patients also describe their symptoms with “lightheadedness, seasickness, instability, rotatory vertigo, etc.” Regarding dizziness, females were significantly more likely to report dizziness compared to males while no significant difference was found for dizziness versus age. Patients experiencing dizziness also reported greater intensity of neck pain compared to those without dizziness. Increasing duration of neck pain was significantly associated with increasing reports of dizziness. Subjects who reported dizziness were significantly more likely to have been involved in an injury. For disability, neck pain patients with dizziness reported significantly more disability (total NDI score) compared to neck pain patients without dizziness.

The authors concluded that neck pain patients with dizziness were significantly more likely to have suffered a trauma injury, experienced greater pain intensity and disability levels, experienced for a longer period of time, compared to neck pain patients without dizziness.

This “study results reinforce the concept of neck pain and disability leading to cervicogenic dizziness/vertigo due to dysfunction of the somatosensory system of the neck.” The basic model presented in this article is that trauma causes “dysfunctional cervical spine structures” resulting in altered “joint and neck mechanoreceptor” function, causing both pain and dizziness.

••••

An article pertaining to the treatment of cervical vertigo, tinnitus and nystagmus appeared in the International Tinnitus Journal in 1998, and was titled (13):

The Influence of Atlas Therapy on Tinnitus

The author, Bernd B Kaute, MD, proposes that the aberrant proprioceptive input of the posterior small cervical muscles to the brainstem are a source of the vestibular-related symptoms (vertigo, tinnitus, and nystagmus). Dr. Kaute suggests that the successful treatment of the aberrant proprioceptive neurology is key to managing these findings and symptoms.

Dr. Kaute states that “atlas therapy” will abate muscular tensions and has been proven to slacken the upper cervical muscles and seems to quiet to normal levels afferent proprioceptive impulses to the brainstem. He notes that “atlas therapy” has the clinical effect of causing reflex driven reduction of hypertonic muscle tone in the neck and back. Importantly, he states that “atlas therapy” is done by “applying specific force to the wing of the atlas,” and that this is often performed by chiropractors. Dr. Kaute makes these statements:

“More than a century ago, Sherrington showed, on his famous decerebrated cats, that touching the dura or stimulating the root of the C2 nerve leads to a slackening of all muscles. Atlas therapy, therefore, seems to work on a similar principle.”

“Through electronystagmography before and after atlas therapy on persons with late whiplash injuries, we discovered that the therapy influences the brainstem and nomalizes a pathological electronystagmogram.”

In this study, “atlas therapy” was conducted on 11 patients with whiplash injuries, with these outcomes:

7 patients experienced a complete recovery of vestibular disturbances.

3 additional patients improved.

1 patient remained unchanged.

Dr. Kaute concluded, “atlas therapy has an effect on the muscles of the neck and lowers their afferences to the brainstem.”

“Irritating these posterior cervical muscles and placing them under tension must precipitate a great afferent input to the vestibular nuclei in the brainstem. This response seems to be one of the origins of idiopathic tinnitus. Diminishing the tension via atlas therapy seems to lower the proprioception and nociception output, leading to normalization of the flow of information to the brainstem and, as a consequence, the lessening of tinnitus.”

“Treating these pathological effects as soon as possible is necessary before the process is definitely established through the plasticity of the neural system.”

“If the input to the brainstem is normalized by atlas therapy, the problem can be resolved.”

••••

SUMMARY:

Hundreds of studies over the past 60 years have established that dysfunctions of the joints and/or muscles of the upper cervical spine can cause the sensation of vertigo. Modern neuroanatomical evidence shows that upper cervical spine mechanoreceptors/proprioceptors fire to the vestibular nucleus as a portion of our human upright balance mechanisms. Additionally, these studies link the functional neurophysiology of the upper cervical spine mechanoreceptors/proprioceptors to not only the vestibular nucleus, but also to the movement of the eyes and to the spinal musculature.

The mechanoreceptor/proprioceptor dysfunction of the upper cervical spine can be ascertained by one appropriately trained in manual diagnostics, static palpation, motion palpation, and/or radiographically assessed vertebral alignment symmetry. Such skills are emphasized in chiropractic college and in post-graduate training courses.

Appropriate and safe treatment of upper cervical spine mechanical problems is a skill that takes much training and initial supervision. The upper cervical spine is anatomically unique, with great mobility coupled with reduced stability. It houses critical nerves and blood vessels. The safe and appropriate management of cervical vertigo requires training, skill, and respect, issue that are stressed in the education of the modern chiropractor.

REFERENCES

1) Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery. 1992 Sep;107(3):399-404.

2) Baloh R, Honrubia V. Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System, Third edition, Oxford University Press, 2001.

3) Jordan P, Ramon Y. Nystagmus and Vertigo Produced by Mechanical Irritation of the Temporomandibular Joint-space. J Laryngol Otol. 1965 Aug;79:744-8.

4) Morgan DH. Temporomandibular joint surgery. Correction of pain, tinnitus, and vertigo. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1973;46(2):27-39.

5) Wright EF. Otologic symptom improvement through TMD therapy. Quintessence Int. 2007 Oct;38(9):e564-71.

6) de Jong PT, de Jong JM, Cohen B, Jongkees LB. Ataxia and nystagmus induced by injection of local anesthetics in the Neck. Annals of Neurology. 1977 Mar;1(3):240-6.

7) Luxon L. “Posttraumatic Vertigo” in Disorders of the Vestibular System, edited by Robert W. Baloh and G. Michael Halmagyi, Oxford University Press, 1996.

8) Hinoki M. Vertigo due to whiplash injury: a neurotological approach. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1984;419:9-29.

9) Hamanishi, Chiaki; Tanaka, Seisuke; Kasahara, Yositaka; Shikata, Jituhiko. Progressive Scoliosis Associated with Lateral Gaze Palsy.

Spine. 18(16):2549, December 1993.

10) Galm R, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E. Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction. European Spine Journal. July 1998: 55-58.

11) Humphreys KM, Bolton J, Peterson C, Wood A. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin. Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, Vol. 1(2) 2002, pgs. 63-73.

12) Ryan GM, Cope S. Cervical vertigo. Lancet. 1955 Dec 31;269(6905):1355-8.

13) Kaute BB. The Influence of Atlas Therapy on Tinnitus. International Tinnitus Journal. 1998;4(2):165-167.